With 7.5 billion humans and more than 70 billion food animals, we are closer to animals than ever before. As the coronavirus pandemic has shown us, we’re also more susceptible to animal diseases.

Approximately 75 percent of new and emerging infectious diseases are zoonotic diseases: spread to humans from animals. But this is less a story of animals causing harm to humans than humans disrupting the environment through agricultural change, says Scott Stoll, MD, board-certified specialist in physical medicine and rehabilitation in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, and cofounder of the Plantrician Project.

“We have absolutely contributed to the creation of these mutated viruses and bacteria that cause epidemics,” says Stoll. “We put animals in very close quarters so that viruses and bacteria can spread more quickly and mutations can happen more rapidly. And then because we’ve also pushed these CAFOs [confined animal feed operations] and production facilities closer to wild animals, it’s easy for the preexisting mutations in wild species to move into the domesticated species.”

As a result, we’ve created the right conditions for the current and future pandemics. Here are five diseases we’ve helped spawn.

Coronaviruses

SARS-CoV2, which is responsible for COVID-19, started as one of hundreds of coronaviruses circulating among animals. But in late 2019 a spillover occurred, most likely at a Chinese wet market where live animals are sold. The virus leapt from animal to human and began to spread quickly, infecting more than 1 million people worldwide by the start of April 2020.

This is not the first time that a wet market has been linked with a coronavirus. In fact, COVID-19 is closely related to another coronavirus known as SARS. That disease emerged in 2002, following a spillover from a bat or an intermediary animal such as a civet. SARS would go on to infect more than 8,000 people worldwide (killing 774) before seemingly disappearing in 2004. While there have been no new cases since then, SARS remains on the World Health Organization’s list of diseases with “epidemic potential.”

Zoonotic Influenza

Every so often, an influenza virus will cross the animal-human divide and infect people. Typically, these viruses are transmitted through direct contact with an infected animal such as birds or pigs or through contact with an animal’s feces. Rarely will the virus spread from person to person. But when it does, the virus has a chance to start a pandemic.

Such was the case most recently with the 2009 H1N1 Flu, which infected 1.4 billion people worldwide and resulted in as many as 575,400 deaths. While it was dubbed “swine flu,” H1N1 likely came from viruses of human, North American pig, bird, and Eurasian pig origins. Pigs served as mixing vessels for the resulting illness and spread the disease to humans via direct contact or airborne means.

"Pigs are often intermediary hosts between other species and humans because of genetic similarities between pigs and humans," explains Stoll. "It's an easier leap to go from swine to humans than other species. With large production facilities of swine, they become the perfect breeding ground for some of these mutations that can easily leap to [farm] workers and production staff, so they become infected and [zoonotic diseases] spread out into the community."

Antibiotic-Resistant Infections

Nearly 80 percent of antibiotic use in the United States occurs in the agricultural sector, with farmers giving animals antibiotics preemptively in an attempt to safeguard them against diseases in crowded conditions. In several other countries, antibiotics are also given to animals to promote growth (a practice recently curtailed in the U.S. by regulations introduced in 2017). While there is no evidence that antibiotics residues in meat directly harm humans, the overuse of antibiotics contributes to the development and spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, such as MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) in both animals and humans. Drug-resistant infections annually affect 2.8 million people, causing 35,000 deaths each year.

"We often forget that the microbiome of animals has an impact on humans," says Stoll. "The food we feed them, the medications they’re treated with, the stress they're under and the cortisol that's secreted from that stress has an impact on the microbiome, causing some bacterial populations to grow versus others, and especially with this constant treatment with antibiotics, we are creating superbugs.”

Campylobacter and Salmonella

The CDC estimates that each year nearly 3 million Americans are infected with one of two types of foodborne illnesses: Campylobacter and salmonella. With the more common Campylobacter, the majority of all infections can be traced back to chickens contaminated at some stage of industrial production. That tainted product goes to market: A 2015 test by the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System found Campylobacter on 24 percent of raw chicken bought from retailers.

Meanwhile, in the case of salmonella, 1.5 percent of whole chickens produced in large plants carry the harmful bacteria, according to the National Chicken Council. Many more outbreaks have been traced to leafy greens that have been fertilized with contaminated manure or irrigated with contaminated water or that have come into contact with contaminated meats during preparation processes.

E. Coli Infections

Causing 265,000 illnesses and about 100 deaths every year, E. coli infections are a byproduct of factory farming. E. coli naturally occurs in a ruminant’s gut, typically in milder strains that our stomach's acidity can kill. However, on factory farms, cows that would normally eat grass are instead fed grain, such as corn. This not only fattens cows up faster, producing more marbling in the meat, but it allows farmers to raise cattle in smaller spaces than if they were grazing. Grain-based diets promote the growth of E. coli that can survive the acidity of the human stomach and cause intestinal illness, such as E. coli O157:H7.

While the most common source of E. coli is beef, there are some well-known cases of E. coli outbreaks from vegetables, such as romaine lettuce in 2018. In that outbreak, the lettuce may have been irrigated with water that had come in contact with a CAFO.

The Takeaway

While we’ll never eliminate infectious diseases completely, we could reduce our risk of exposure to zoonotic diseases and harmful bacteria by reducing our reliance on animal agriculture. “It’s my sincere hope that out of this pandemic, we’ll know better and we can do better,” says Stoll.

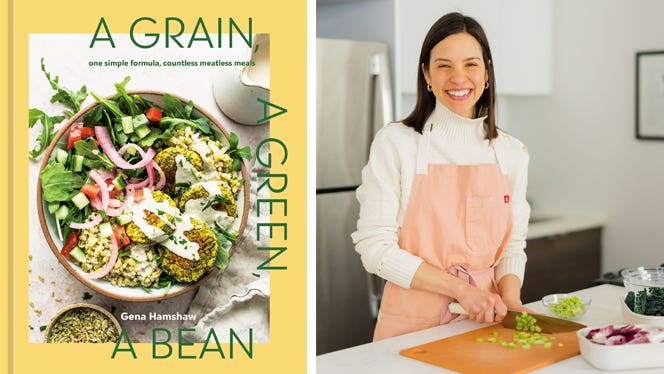

Ready to get started? Check out our Plant-Based Primer to learn more about adopting a whole-food, plant-based diet.

Related News

Get Our Best Price On The Forks Meal Planner

Forks Meal Planner takes the guess work out of making nutritious meals the whole family will enjoy.

SAVE $200 ON OUR ULTIMATE COURSE

Join our best-selling course at a new lower price!